Lecture on Social Justice and Sustainable Development

- Speaker: Fr. Philip J. Chmielewski, S.J.

Professor and Sir Thomas More Chair of Engineering Ethics, Loyola Marymount University, Los Angeles California, USA - Respondent: Prof. Wu Kaming

Associate Professor of Department of Cultural and Religious Studies, the Chinese University of Hong Kong

Replay Video

Download Full Version of this summary

Summary

The term “social justice” can mean different things to different people. “Sustainability” and “development” have been traditionally identified with profit and GDP. As professor of Engineering Ethics and a Catholic, Professor Philip Chmielewski presents what social justice means in the Catholic tradition. He also charts a proper understanding for sustainability and development in the 21st Century, if we are to survive, thrive and mitigate systemic risks. A close observer of Hong Kong, Professor Chmielewski considers some ways principles of social justice could be applied to Hong Kong, and how Hong Kong could respond to the global imperative of sustainable development.

Two Key Dimensions of Social Justice

In 1931 Pope Pius XI issued the encyclical Quadragesimo Anno (On Social Reconstruction) which laid out solidarity and subsidiarity as two key principles upon which a social order facing existential threats can be rebuilt. Both concepts “have been influential beyond Catholic circles, including in European Union law which considers them key principles.” (The Wall Street Journal, February 5, 2021)

Solidarity gave its name to the famed Polish workers’ movement. In his 1987 encyclical Sollicitudo Rei Socialis (On Social Concern), Pope John Paul II noted: “Solidarity is most important on the international level. International interdependence must be transformed into the virtue of solidarity by recognizing that the goods of creation exists to serve the needs of all.” In the 21st century, in Laudato Si’ (On Care for Our Common Home), Pope Francis extends the principle further and speaks of the “intra- and intergenerational common good as a result of solidarity with the earth.” Solidarity is not just a commitment to others around the world, but also to future generations.

What is Subsidiarity?

Professor Chmielewski quotes again from Quadragesimo Anno, #79: “Just as it is gravely wrong to take from individuals what they can accomplish by their own initiative and industry and give it to the community, so also it is an injustice and at the same time a grave evil and disturbance of right order to assign to a greater and higher association what lesser and subordinate organizations can do. For every social activity ought of its very nature to furnish help to the members of the body social, and never destroy and absorb them.” In other words, what individuals can accomplish by their own initiative and efforts should not be taken from them by a higher authority. Catholic social teaching teaches respect for individuals, and the groups that they form to improve their lives so they can live fully.

Subsidiarity is practical. Maria Catherine Cahill draws out five political purposes from the social teaching of the Catholic Church: increased participation, more proximate decision-making, better outcomes (it’s what the people need), more efficient decision-making, and alleviating the state’s administrative burden. Professor Chmielewski describes social justice as a functional structure, a necessary set of conditions (made up of laws and customs, policies and practices of the community) wherein each member can flourish, and engage with one another. When we do things together, we evolve a common responsibility to one another. Social justice promotes the common good, “never the private good of individuals at the expense of the community.”

In “Capitalism After the Pandemic: Getting Recovery Right,” the economist Mariana Mazzucato posits the changes that need to be made: “This economy would be more inclusive and sustainable. It would emit less carbon, generate less inequality, build modern public transport, provide digital access for all, and offer universal health care.” The economy should be driven by value—what we do for one another—not just by profit. She adds: “The road to a more symbiotic partnership between public and private institutions begins with the recognition that VALUE is created collectively.

Next Professor Chmielewski introduces the work of Elinor Ostrom, the first woman to win the Nobel prize in economics, and who pioneered designs for governing the commons. She gave examples of Common Pool Resources (such as fish stock, timber, coal) that are non-excludable, but rivalrous (i.e., subject to depletion), and other public goods (e.g., broadcast, air, herd immunity) that are non-excludable and non-rivalrous. In Governing the Commons in China, Yan Zhang studied the upper Mekong. She said: “The concept of commons refers to anything held in common, from tangible resources (such as water and biodiversity) to intangible (such as ethnic cultures).” To resolve conflicts and so current and future generations can live, there is a need to organize the commons. Professor Chmielewski highlights three of Ostrom’s guidelines: inclusive decision-making process; recognized rights to organize, and “nested enterprises.”

The design calls for multiple layers for appropriation/provision (people have to agree on what is being shared and how); monitoring/enforcement (develop a system, carried out by community members, for monitoring members’ behavior); conflict resolution; and governing (use graduated sanctions for rule violators; provide accessible, low-cost means for dispute resolution).

Ostrom wrote in Understanding Institutional Diversity: “Since most ecological systems are nested from very small local ecologies to those of global proportions, following this principle requires a substantial investment in governance systems at multiple levels—each with some autonomy, but each exposed to information, sanctioning and actions from below and above.” This system—based on subsidiarity, transparency and conflict resolution—builds responsibility for governing the common resource from the lowest level up to the entire interconnected system.

Sustainability = “Triple Bottom Line”?

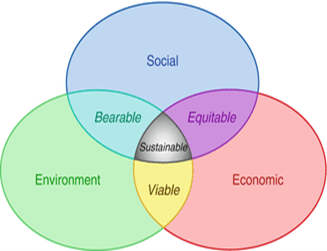

Gro Harlem Brundtland chaired the UN Commission that produced Our Common Future published in 1987. The Brundtland Report introduced a new model of interconnecting social, environmental and economic well-being. Sustainability lies at the very core. Profit-driven economic development increases social inequality and devastates the earth. To survive and thrive, there needs to be a new triple bottom line: environment, work, and voice.

Professor Chmielewski characterizes the social as “voice”—what people say about their world can be said, will be listened to, and given response to. People matter more than profits. “Public” changes meaning too, in that other life and non-forms count in their participation in public goods.

Development is not GDP

17 Sustainable Development Goals were adopted by all UN member states in 2015, including China.

Brundtland lists six key “entry points” where collaborative action can accelerate progress towards the Goals:

- Strengthening human well-being and capabilities;

- Shifting towards sustainable and just economies;

- Building sustainable food systems and healthy nutrition patterns;

- Achieving energy decarbonization and universal access to energy;

- Promoting sustainable urban and peri-urban development;

- Securing the global environmental commons.

Professor Chmielewski quotes extensively from the 2019 Global Sustainable Development Report (GSDR). Chief among the recommendations: actions must be taken to eliminate deprivations, and build resilience, especially through targeted interventions where poverty and vulnerability are concentrated. The old view of GDP growth will not address the multidimensional nature of poverty (evidenced by the lack of education, safety, water, food security, clean and reliable energy, health care, etc.) The GSDR recognizes that people are the greatest asset in the fight for sustainability: “Furthering human well-being and protecting the earth’s resources require expanding human capabilities …, so that people are empowered and equipped to bring about change.”

Possibilities for Hong Kong

It may come as a surprise that Hong Kong, despite her many current trials, has something to teach about sustainable development because of the city’s “naturbanity” and significant biodiversity. Professor Chmielewski also names various local NGOs that promote sustainable development, such as Designing Hong Kong, UN Sustainable Development Solutions Network (Hong Kong chapter) and Civic Exchange. The SAR government promised a carbon neutrality strategy by mid-2021. Hong Kong does not lack civic proposals and even government researches, but as Professor Wu Ka-ming noted: people have expressed; scholars have consulted; think tanks have produced policy recommendations, but the government does not listen, and there is no result.

Response by Professor Wu Ka-ming

As a social anthropologist, Professor Wu asks how Catholic Social Teaching can help us think through the “land developers’ hegemony” in Hong Kong. Professor Wu gives examples of stark social inequality: sub-human living quarters where poor people are prone to disease and infection. She appreciates Professor Chmielewski’s talk on subsidiarity across disciplines. But the Church’s advocacy of participation, personal regard, social justice, and the common good also feels surreal in Hong Kong. A case in point: the government-touted “Lantau Tomorrow Vision” will dump sand to build a floating island which will be submerged by sea-level rise and severe weather crises according to scientists’ projections.

Professor Wu refers to her recent article, “Infrastructure and its discontent: Structures of feeling in the age of Hong Kong-China dis/connection,” in which she observed the changing social sentiments of Hong Kong’s young people. As the SAR government invests heavily in infrastructure projects to better connect with the mainland, and encourages young people to move to the Greater Bay Area, young people feel hopeless about a system that enriches only a very small minority. Some expressed their anger by destroying the city’s finest infrastructures. Hong Kong cannot wait. Take for instance the recent scrapping of a waste levy that has been in deliberation for 20 years. How can sustainable engineering bring about equality, and benefit the disadvantaged now?

Engineers are bound by code of conduct in different fields to assess and disclose risks, and work with other stakeholders to reduce risks, Professor Chmielewski maintains. Developers are keen on making profit, but they have not been attentive to new economic developments. Professor Chmielewski refers to influential economists who have come to the conclusion that governments and markets are not sufficient. Civil society needs to take part (Raghuram Rajan, The Third Pillar). Corporations must look not only at profit-margins and stockholders, but also those affected by their decisions (Colin Mayer). Even if those with more power ignore history and economics, they face the same threats of disease, climate change, food security, mass migration ….

Professor Chmielewski draws inspiration from a sign at a Chicago bookstore long associated with social causes: Books matter, people care, change is possible. Discourse matters. Acts of solidarity and kindness influence others. Change is possible. Conversely, when (young) people see that promises/texts are not kept, and care is absent, they do not give it; if they do not see change as possible, they may break things. Professor Wu also invokes the new “doughnut economic model,” a development model that respects human wellbeing and ecological ceiling.

Dr. Cynthia Pon, the moderator, gives the example of the World Day of the Poor, instituted by Pope Francis in 2016. Every year the Church brings together the marginalized, provides a forum, empowering them, trusting in their capacity to organize and work for the common good. In the struggle between old and new economic paradigms (one top-down, monologic; the other participatory, discursive and pluralistic), it seems Hong Kong is moving toward a regressive model. Two things, however, give hope: 1) young people and civil society are studying seriously, not just within academia; 2) Professor Chmielewski presents “forgiveness” as part of discursive engagement (Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition). She affirmed forgiveness as a widely regarded value that members of a society can learn to create together.

Dr. Anselm Lam, Director of the Centre for Catholic Studies at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, shares Professor Wu’s “impatience” with incremental changes, and the demand for structural change. He asks what we can do to spread Catholic Social Teaching within civil society to bring about conversion, social justice.

Professor Chmielewski reports that one advantage Hong Kong has is that the world is watching and cares about what is happening here. He also gives the example of Black history. Black people were invisible; but across the United States, there are changes taking place toward greater diversity, equity, and inclusion. In Hong Kong, what are students and young people reading and studying? Are they doing so in a way that effects change, across boundaries, unto future generations?

Please click for the full version of this summary or Video of this online lecture.